Is Taiwan Arming Youth Ballplayers with AI?

The story of a Little League champion turned tech czar offers insights

For a country widely known for its dominance in semiconductor manufacturing, Taiwan is actually quite behind in the integration of technology in baseball.1 So, no, while we are seeing “AI-powered” baseball camps and other innovations in the U.S., even if mostly gimmicky, the Taiwanese are not yet arming youth players with AI.

The real news: Basegarden, a youth baseball foundation focused on rural Taiwan, partnered with tech company MetaAge to donate laptops to rural schools and present a seminar on AI. While not as provocative, this small step is arguably more significant in a culture where, historically, athletics and academics are separated at a young age.

Let’s rewind 50 years. Youth baseball development was largely a nationalist initiative in the 1970s. Chiang Kai-shek’s authoritarian government, still fixated on “taking back the mainland” and decades away from democratizing, saw its diplomatic influence start to crumble. It needed a way to solidify its legitimacy and found this in what I will call the “youth baseball arbitrage.”2 It was a formulation to take advantage of the U.S.’s relaxed attitude toward training young players and its concurrent fascination and coverage of world competition in Little League Baseball.

The nationalist impulse

After sending a Taichung team that won the Little League World Series (LLWS) title in 1969 and receiving international coverage, the winning formula became simple in the 1970s:

Field a team to play in the LLWS;

Display dominance (i.e., win a lot);

Receive American “international” coverage;

Feel like a strong nation;3 and

Repeat step 1.

This was evidently a self-sustaining cycle and resulted in a win-at-all-cost mentality. At worst, it fostered unsavory tactics discussed in Andrew Morris’s Colonial Project, National Game.4 At best, the national obsession spurred specialization and generated a pipeline of young winners. Teams from Taiwan won 17 titles in a three-decade stretch starting in 1969, not to mention the wins at the Senior and Big League levels.

Exactly how Taiwan or Chiang’s government was portrayed seemed secondary to the fact that there was any coverage at all. All press was good press at that point. Chiang’s government was expelled from the United Nations in 1971, and Taiwan remains unrepresented in many international organizations to this day.

Nonetheless, the national baseball craze produced cohorts of top players like Yuen-Chih Kuo but also byproducts like the unlikely story of Cheng-Wen Wu.

A tale of two champions

Yuen-Chih Kuo, or Genji Kaku as he is known in Japan,5 was born in 1956 in Taitung, southeastern Taiwan. He was a pitching phenom who caught national attention in 1969, the year Taiwan held a national team identification tournament to organize a national superteam.

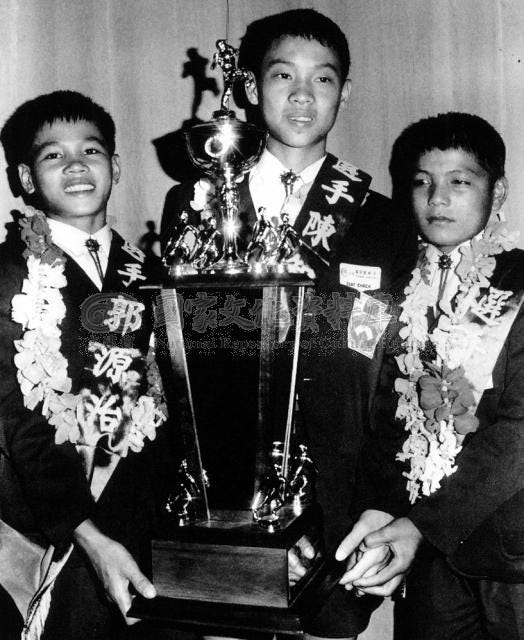

Kuo excelled on the mound, reportedly throwing a 13-inning, 220-pitch(!) complete game at one point, and batted .350 in the tournament to earn a spot on the Taichung Golden Dragons. The Taiwanese all-star team won the Far East region and then powered past Canada, Ohio, and California to win the 1969 LLWS title. This was the first ever championship won by a team from Taiwan.

Kuo’s baseball career took off a few years later. He signed with the Chunichi Dragons in 1981 and never looked back. His fastball reached 151 km/h (about 94 mph) in his NPB debut. Over his 16-year career in Japan, Kuo recorded 106 wins, 116 saves, a 3.22 ERA, and 1,415 strikeouts. He was inducted into the Taiwanese Baseball Hall of Fame in 2019.

Many players that were part of the pipeline of champions, like Yuen-Chih Kuo, came from rural and indigenous communities. They devoted their schooling years almost exclusively to baseball. Most, unlike Kuo, would not reach his level of success, or anywhere close to it. For a Taiwanese athlete trained for professional baseball, Kuo achieved the traditionally ideal outcome.

Cheng-Wen Wu, our second protagonist, was born in 1958 in Tainan, southern Taiwan. Like many of his classmates, he played baseball at school. In 1971, two years after Taichung’s historic win, Wu’s Tainan Giants entered the LLWS as the Far East regional champions and also dominated. A standout pitcher, Wu threw a shutout in the 11-0 win against Hawaii in the semifinals. In the championship game, Tainan defeated Gary, Indiana, led by future MLB player and manager Lloyd McClendon.

The glorious win in Williamsport may have turned out to be the least remarkable feat in Wu’s life in the context of Taiwanese history. After all, it was replicated by eight other Taiwanese teams over the next decade.

After his baseball career, which did not extend much further, Wu received degrees in electrical and computer engineering, first from the prestigious National Taiwan University (NTU) then from the University of California, Santa Barbara, where he earned his master’s and Ph.D. Following his extensive schooling, Wu joined the faculty of the National Tsing Hua University (NTHU) and eventually became vice president of NTHU. He was one of eight candidates running to become president of his alma mater NTU.

In 2024, Cheng-Wen Wu became minister of the National Science and Technology Council, stewarding the research and development of some of the world’s most advanced technology. As Taiwan’s “tech czar,” Wu oversees the funding of academic research and the development of industrial complexes like the famed Hsinchu Science Park.

Wu’s career path could not have differed more from Kuo’s. Even though his baseball career peaked early, his integration into the world outside of baseball is truly a blueprint for educating young players. Five decades after their shared experiences as Little League champions, they are linked once again in the modern age.

Competing futures of youth baseball

The thread that brings Kuo and Wu together is another ballplayer, former CTBC Brothers outfielder and Hualien native Szu-Chi Chou. Chou was born in a small town in Hualien called Guangfu, or Fata’an in Amis. He is a three-time recipient of a youth baseball scholarship established by Yuen-Chih Kuo.

According to Chou, he was only able to afford a left-handed glove because of the scholarship. Chou’s professional baseball career spanned 20 years. He is a four-time Taiwan Series champion (all with the CTBC Brothers / Brother Elephants) and MVP in 2012.

Inspired by Kuo’s philanthropy, Chou founded Basegarden in 2013 to support youth baseball players in rural Taiwan. However, unlike Kuo’s scholarship, Basegarden focuses on the players’ academic pursuits, often outside of baseball. It has partnered with TSMC to offer career resources and broaden professional opportunities, for example.

So, a Kuo protege is now helping the next generation of baseball players build tech literacy and diversify their career paths. In essence, he is working to produce more Cheng-Wen Wus. The future is bright for Taiwanese youth baseball players who will all become well-rounded students and excel in other fields beyond their playing careers … right?

Not exactly. For one thing, the nationalist impulse is still there. After Team Taiwan won the 2024 Premier12 title, EasyCard Corporation announced it would donate to the Taiwan Indigenous Baseball Development Association, with the explicit goal of producing future indigenous players that can bring home more golds.

The Taiwanese want to see their country win. Players are viewed as tools to help achieve that goal, and indigenous communities have historically been the perfect toolboxes to draw from. That means continued specialization into sports for marginalized kids with little pathways to alternative careers—the opposite of what Basegarden is aiming to achieve. The irony is that when it comes to putting Taiwan back on the map, winning countless Little League titles seems pretty ineffective.

Will there be another Yuen-Chih Kuo? Almost certainly.6 The more important question is: Will there be another Cheng-Wen Wu? A Little League champion turned tech czar (or industry titan or leading artist)? We shall see in a few years, or decades.

Covering the bases

The TSG Hawks have re-signed slugger Steven Moya to a one-year deal. Hawks right-handed pitcher Spenser Watkins announced his retirement. Baseball America projects left-hander Wei-En Lin to be the Athletics’ No. 4 starter in 2029. Former Chicago Cubs pitcher Jen-Ho Tseng, who was non-tendered by the Rakuten Monkeys, reportedly agreed to terms on a deal with the Wei Chuan Dragons.

Statcast (using the PITCHf/x camera system, then the TrackMan radar system) was installed in all 30 MLB stadiums in 2015; as of 2025, two of the six CPBL teams do not yet use TrackMan, and one uses just a portable unit.

With the majority of the country, some 85% of the population, having lived through Japanese rule and embraced what was known to them as a Japanese game, Chiang’s newcomer government, explicitly anti-Japanese, saw its usefulness and reluctantly accepted baseball.

Whether this nation meant “Free China” (as in the grand project supported by Chiang’s regime who arrived just two decades prior) or “Taiwan” (as in the physical land with which most countrymen were inclined to identify), or some combination of the two national identities, was contentious and remains a debatable topic.

Kuo’s name has also been translated as Yen-Tsu Kuo, as he was registered in the Little League system.

National resources continue to be poured into player development. Plenty of professional players have performed at the highest level in Japan and beyond.